Alchemy

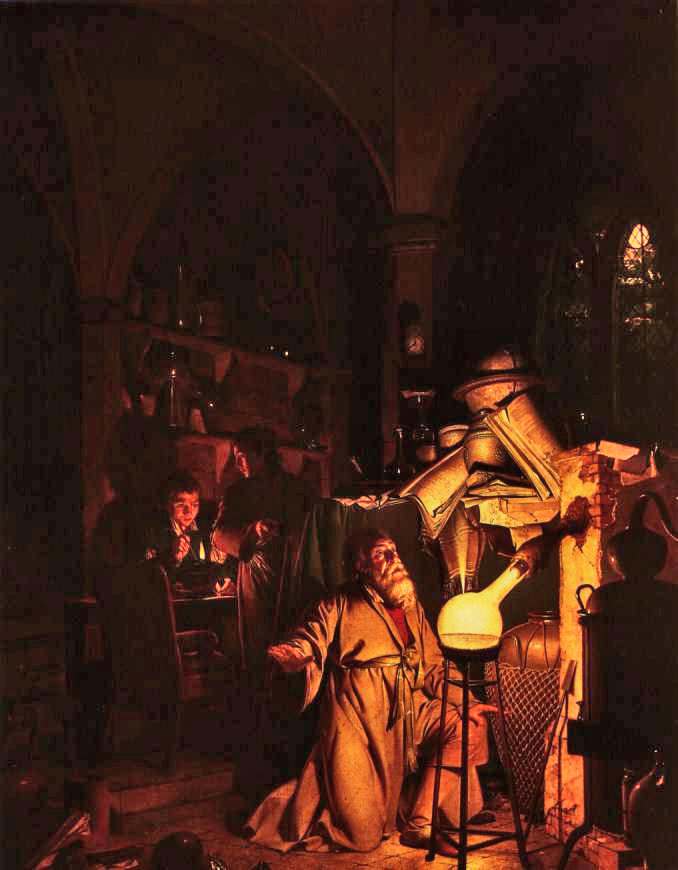

Alchemy is an influential philosophical tradition whose early practitioners’ claims to profound powers were known from antiquity. The defining objectives of alchemy are varied; these include the creation of the fabled philosopher’s stone possessing powers including the capability of turning base metals into the noble metals gold or silver, as well as an elixir of life conferring youth and immortality. Western alchemy is recognized as a protoscience that contributed to the development of modern chemistry and medicine. Alchemists developed a framework of theory, terminology, experimental process and basic laboratory techniques that is still recognizable today. But alchemy differs from modern science in the inclusion of Hermetic principles and practices related to mythology, religion, and spirituality.

The best known goals of the alchemists were the transmutation of common metals into gold or silver, and the creation of a “panacea,” a remedy that supposedly would cure all diseases and prolong life indefinitely; and the discovery of a universal solvent. Modern discussions of alchemy are generally split into an examination of its exoteric practical applications, and its esoteric aspects. The former is pursued by historians of the physical sciences who have examined the subject in terms of proto-chemistry, medicine, and charlatanism. The latter is of interest to the historians of esotericism, psychologists, spiritual and new age communities, and hermetic philosophers. The subject has also made an ongoing impact on literature and the arts. Despite the modern split, numerous sources stress an integration of esoteric and exoteric approaches to alchemy. Holmyard, when writing on exoteric aspects, states that they can not be properly appreciated if the esoteric is not always kept in mind. The prototype for this model can be found in Bolos of Mendes’ second century BCE work, Physika kai Mystika (On Physical and Mystical Matters). Marie-Louise von Franz tells us the double approach of Western alchemy was set from the start, when Greek philosophy was mixed with Egyptian and Mesopotamian technology. The technological, operative approach, which she calls extraverted, and the mystic, contemplative, psychological one, which she calls introverted are not mutually exclusive, but complementary instead, as meditation requires practice in the real world, and conversely.

Nuclear transmutation

In 1919, Ernest Rutherford used artificial disintegration to convert nitrogen into oxygen. From then on, this sort of scientific transmutation is routinely performed in many nuclear physics-related laboratories and facilities, like particle accelerators, nuclear power stations and nuclear weapons as a by-product of fission and other physical processes.

The synthesis of noble metals enjoyed brief popularity in the 20th century when physicists were able to convert platinum atoms into gold atoms via a nuclear reaction. However, the new gold atoms, being unstable isotopes, lasted for under five seconds before they broke apart. More recently, reports of table-top element transmutation—by means of electrolysis or sonic cavitation—were the pivot of the cold fusion controversy of 1989. None of those claims have yet been reliably duplicated.

Synthesis of noble metals requires either a nuclear reactor or a particle accelerator. Particle accelerators use huge amounts of energy, while nuclear reactors produce energy, so only methods utilizing a nuclear reactor are of economic interest.